APIs didn’t pop up overnight; they’ve been around for a while, quietly doing the “boring” work that keeps the internet stitched together. What’s changed is that people outside of engineering circles are finally stumbling upon the term and wondering what it even means.

An API, short for “application programming interface”, is how different pieces of software communicate with each other, not conversationally/creatively, more like strict instructions. These define what can be requested, how those requests have to look, and the types of responses that come back.

You likely interact with APIs every day without even knowing it, when an app pulls up prices, syncs account data, loads your doomscrolling feed, an API is usually involved. Modern software doesn’t really exist in insolation anymore, it’s put together with a bunch of smaller pieces that APIs are keeping together.

IP rotation, city and carrier targeting,

sticky sessions — control it all via API

It sounds simple on paper, one system sends a request, the other responds, and everyone moves on, but, in practice, there’s a smorgasbord of rules layered on top of rules, and there’s plenty of room for something to go wrong, especially when scale is involved.

Utilizing an API isn’t just “getting data”, think of it more as agreeing to a contract. You ask in the format that’s expected, you stay within the limitations, and you accept the responses you’re given. If you stray from said limitations, the API doesn’t argue with you, it just stops cooperating.

How APIs Work

In its simplest form, an API works on a request/response cycle. A client sends a request to an endpoint, the server processes it, a response is sent back. That response could be data, an error, or sometimes, nothing useful at all.

Requests typically include parameters that tell the API what it is you’re looking for. Responses come back in a structured format, most commonly JSON, but the format itself isn’t the important bit, consistency is. APIs rely on predictable structures so systems don’t have to guess as to what they’re receiving.

APIs expose specific endpoints, which are fixed paths that accept certain types of requests. In simpler terms, you can’t ask for anything you want, and you can’t ask it however you want either. If the endpoint doesn’t exist, or the method is wrong, the API just won’t work the way it’s expected to.

This is all typically hidden from end users. Apps handle it in the background, when everything works as intended nobody notices. But, when something breaks, that failure can feel sudden and confusing, even though the issue has probably been quietly brewing behind the scenes.

Common Types of APIs

There are many API types, but let’s stick to the common ones:

- REST APIs: The most common API type, they’re pretty simple, stateless and predictable. All requests made are independent, and the server isn’t required to remember anything about any previous interactions.

- GraphQL APIs: These APIs take a different approach. Instead of hitting multiple endpoints, you ask for the exact data you want in a single request. This flexibility can be great, but it makes it easier to create inefficient or complex queries if you don’t keep everything in check.

- SOAP APIs: These are older and more rigid, relying on strict schemas and heavier message formats. While they might feel dated, they’re still very much used in industries where stability is more important than speed or convenience.

Why APIs Are Used

APIs exist because having to build everything from scratch is simply an inefficient time sink.

They allow companies to expose specific functions without giving up access control over their systems. They also allow developers to build on top of existing services instead of flat out recreating them. This also allows different products to integrate with other products without having to know how everything’s working under the hood.

APIs also help keeping systems loosely coupled; a component can change without forcing everything to change along with it, at least in theory. This separation makes maintenance less of a chore and allows teams to move faster without breaking the functionality of another product’s features.

Without APIs, modern software would be slower to build, harder to maintain, and far more fragile than it already is.

APIs in Modern Web Applications

Most web apps today are really just a collection of several smaller services pretending to be a single product.

Frontend sends requests to an API, it forwards those requests to other services, they interact with databases, authentication systems, or third-party tools, then pass said responses back up the chain.

If everything functions in the intended fashion, the user never sees any of this. The app feels responsive and smooth. When an API fails, the entire experience enters a downward spiral, even if only a small piece of the equation is what broke.

APIs are crucial. They aren’t some flashy tech, and some people don’t even know what they are, but they’re the backbone of how modern apps function, especially at scale.

Public APIs vs Private APIs

Not all APIs are actually meant to be used by everyone. Some are exposed intentionally, while others stay firmly sealed behind closed doors.

Public APIs are designed for external use by the general public. They’re well documented and usually come with a set of rules on how often you can use them and what you’re allowed to do with them. If a company wants third parties to build on top of their product, this is how they do it. For example, our Twitter scraper made use of X’s API rather than trying to retrieve posts the hard way.

Private APIs are the exact opposite. They intentionally hide how internal systems talk to each other. No public docs, no marketing pages, no expectations that outsiders should even know of their existence. They’re used to power things like internal dashboards, background jobs, and communication between services.

This distinction is important since it changes how APIs are set up and maintained. Public APIs focus on stability and backwards compatibility, private APIs can afford to move quicker, break things and evolve without warning. When people complain about an API being “bad”, they’re probably handling a private one like it was meant to be public.

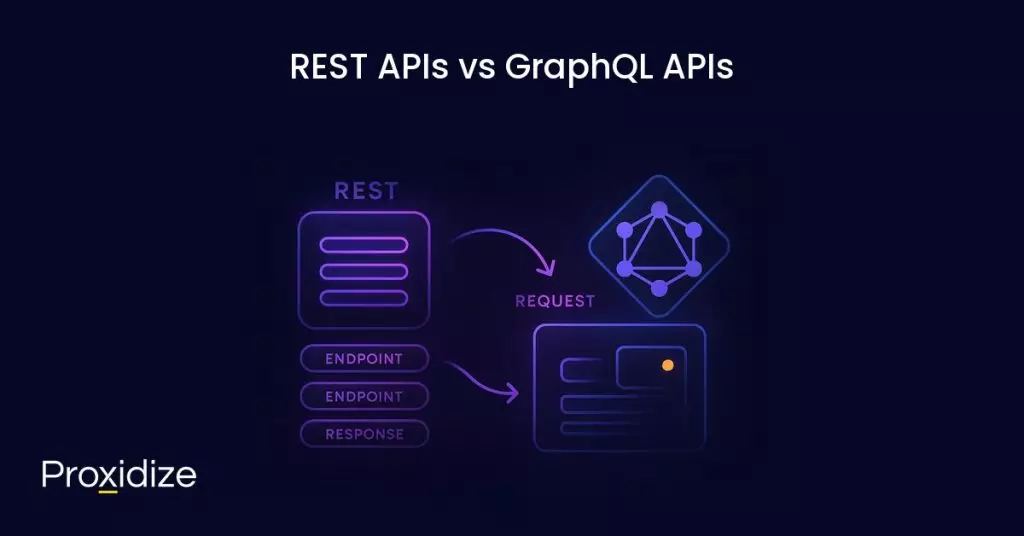

REST APIs vs GraphQL APIs

REST APIs are the default for a reason. They’re predictable, simple, and easy to reason with. You hit a specific endpoint, you get back a specific response, and every request stands on its own. The majority of APIs you’ve ever interacted with tend to fall into this category.

GraphQL takes a different approach. Instead of hitting multiple endpoints, there’s usually just one. You tell the API what data you want and it responds with only that; no more, no less. This can be a powerful asset when clients need very specific data shapes. GraphQL comes with trade-offs, though. It shifts more responsibility onto the client, Poorly designed queries can be expensive, caching becomes harder, and debugging can get real messy if nobody’s paying attention.

Neither one of these is inherently better than the other. REST works well with stable and predictable data models, while GraphQL shines when clients vary widely in what they require. Most problems don’t come from the API itself, but from choosing one because it’s “trendy” and not use case relevant.

How APIs Are Authenticated

APIs don’t hand out data to just anyone. Especially today, data is valuable. As with so many things, there’s almost always some type of authentication involved in interacting with APIs.

The simplest method is an API key, a token that accompanies each request to identify who’s calling the API. It’s easy to use, rotate, and misuse if it accidentally leaks. This is why said keys are often paired with restrictions and usage limits.

More sensitive APIs rely on tokens that are tied to user accounts or applications. OAuth is a common example, instead of exposing any credentials, the API issues “time-limited” tokens that can be refreshed or revoked. It makes things a bit more complex, but it also adds control.

Authentication exists to protect all parties. The API provider gets to limit abuse and track usage and the consumer gets access without having to share any passwords. When authentication is poorly implemented, it either devolves into a security risk or a usability nightmare — sometimes both.

Common API Use Cases

APIs are involved to some degree whenever software needs to talk to something else, without human involvement. They’re used to sync user accounts across platforms, pull data into dashboards, process payments, send notifications, etc. The apps you use on your mobile almost entirely rely on APIs to function, as do most modern websites.

You can also think of APIs as the glue that connects a bunch of services that weren’t explicitly designed to work together. A CRM talks to an email tool, an ecommerce store talks to a payment service. None of these systems ever need to know how the others are built, they just need to know how to ask for what they need.

Once an API is integrated into a workflow, they tend to disappear from view. Everything just works, until it doesn’t, which is usually when people realize how much their systems depend on them.

What Can Go Wrong With APIs

APIs fail in boring ways. That’s usually the issue. Endpoints can change without warning, responses come back slower than expected, rate limits kick in at the worst possible time — sometimes an API just starts returning errors and nobody even knows until users start complaining.

A common culprit is versioning. When an API gets updated, maybe a field decides to disappear. When that happens something downstream suddenly stops working because it’s missing a crucial piece of information. Authentications can also just expire, documentation can be outdated; small changes can compound very quickly, especially when a bunch of systems depend on one another.

Most API issues aren’t dramatic. More often than not they’re subtle, persistent, and flat out annoying. The trouble is that those are also the type of problems that slowly erode trust in a system over time.

When API Gateways Enter the Picture

Once you have a bunch of APIs, multiple consumers, and shared rules around access, it becomes tedious to manage everything individually. This is when API gateways come into play. API gateways centralize routing, authentication, and limits so those concerns aren’t repeated across services.

API gateways aren’t mandatory. There are many systems that work well without one. However, once a system reaches a certain scale, having a single point from which to enforce rules and manage traffic becomes both practical and convenient.The key is restraint. An API gateway should simplify the system and not become another layer nobody wants to touch.

Conclusion

APIs are the backbone of modern software development. They’re how different features can communicate with each other without explicitly being designed to do so. It also makes loose integration possible, with multiple different pieces of software all still able to communicate despite the underlying code being updated.

Key takeaways:

- APIs are a set of structured ways to communicate with a piece of software

- Most APIs need you to stick to a set of rules like how many times you can request data

- APIs exist to keep a consistent method of communication regardless of how code changes behind the scenes

- Almost all modern apps use APIs to communicate internally and with other services

- An API gateway is a centralized way to enforce rules and manage traffic in a system that has grown large enough to need one

As a consumer, you’ll almost never be aware of an API unless it stops working. Even a small break can have serious knock-on effects downstream. When they’re designed well, you don’t notice them in the background. When they’re not, everything built on top of them feels fragile.